The direct church action model of baptism

This is the eighth in a series of blog posts in which we are seeking to answer one overarching question—is a properly qualified administrator essential to valid baptism? The first post introducing the series can be found here.

We’re now considering the more immediate question, is baptism an act of a local church? Some Baptists have insisted that it is, and they have explained precisely how baptism is performed by a local church in a few different ways. Three distinct models of congregational action have been proposed:

The direct church action model - Local churches may not delegate their authority to admit candidates to baptism. The validity of baptism is dependent on the personal presence and action of the congregation in each case.

The ordination model - Local churches may delegate their authority to admit candidates to baptism, but only to ordained ministers. The validity of baptism is dependent on the baptism and ordination of the administrator.

The appointment model - Local churches may delegate their authority to admit candidates to baptism to any member appointed by the church. The validity of baptism is not dependent on the baptism or ordination of the administrator.

In this post, we will consider the first of these models, what I have termed the direct church action model.

Proponents of the direct church action model assert that in order for a baptism to be valid, a local church must both act to approve the baptism and be physically present when it is administered. Any baptism without the direct action and presence of a local congregation is invalid. The authority to admit candidates to baptism belongs solely to local churches, and this authority cannot be delegated even to ordained ministers, apart from the personal presence and action of a congregation in every case.

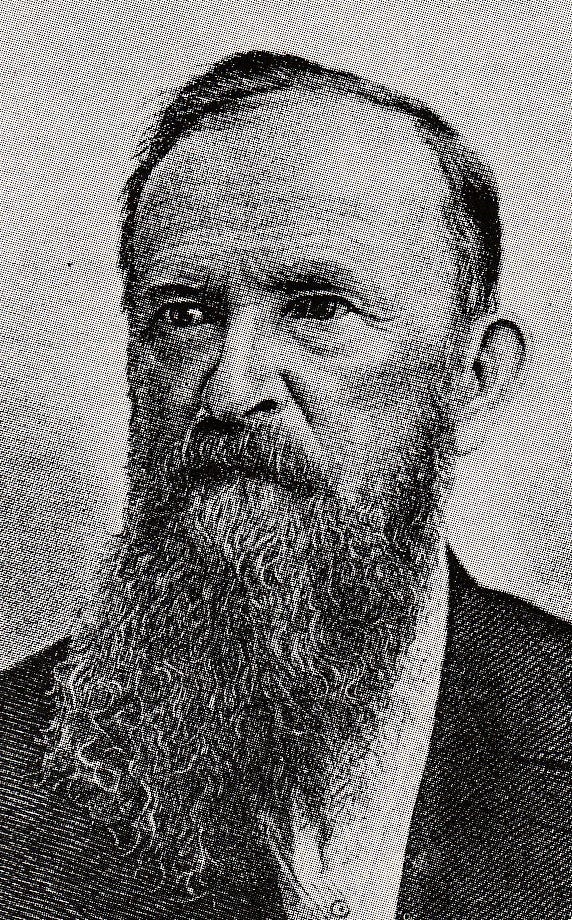

Although few Baptists today would pronounce such stringent requirements on the administration of baptism, one very influential Baptist of the 19th century did advocate this view—J.R. Graves, the champion of Landmarkism.

In 1880, Graves published a book entitled Old Landmarkism: What Is It?, in which he sought to define the principles of the movement he had fiercely promoted for several decades. In the preface, Graves emphasizes the unique and foundational role he played in the Landmark movement:

I put forth this publication now, thirty years after inaugurating the reform, to correct the manifold misrepresentations of those who oppose what they are pleased to call our principles and teachings, and to place before the Baptists of America what “Old Landmarkism” really is …

I think it is no act of presumption in me to assume to know what I meant by the Old Landmarks, since I was the first man in Tennessee, and the first editor on this continent, who publicly advocated the policy of strictly and consistently carrying out in our practice those principles which all true Baptists, in all ages, have professed to believe.

Be this as it may, one thing is certainly true, no man in this century has suffered, or is now suffering, more than myself “in the house of my friends,” for a rigid maintenance of them.

(Graves, Old Landmarkism, 1880, p. xiii-xiv, https://books.google.com/books?id=k04NAAAAYAAJ)

Graves clearly intended his book to be a defining statement of the true principles of Landmarkism. Although he largely succeeded, some of what he wrote actually reflected his own personal views and not those of the wider movement.

One example of Graves’ idiosyncratic views is his adamant assertion that the authority of a local church to baptize cannot be delegated:

The church is alone authorized to receive, to discipline, and to exclude her own members.

This power, with all her other prerogatives, is delegated to her, and it is her bounden duty to exercise it; she can not delegate her prerogatives.

“Quod delegatur non delegatum est” is a legal maxim as old as the civil code. What is delegated can not be delegated. She can not authorize her ministers to examine and baptize members into her fellowship without her personal presence and action upon each case. A minister, therefore, has no right, because ordained, to decide who are qualified to receive baptism and to administer it. Their ordination only qualified them to administer the ordinances for a church when that church called upon them to do so. A minister has an equally just right to administer the Lord’s supper to whom, and when, and where he pleases, and one act would be as null as the other …

It is the inalienable and sole right and duty of a Christian church to administer the ordinances, Baptism, and the Supper.

That these ordinances were designed to be of perpetual observance, commemorating specific and important events or acts in the work of Christ, no intelligent Christian will deny. The rites and ordinances of an institution belong, unquestionably, to that institution, and may be rightly said to be in it. I mean by these expressions that they are under the sole control of the organization; they can be administered only by the organization as such, and when duly assembled, and by its own officers or those she may appoint, pro tempore.

(Graves, Old Landmarkism, 1880, p. 48-51, https://books.google.com/books?id=k04NAAAAYAAJ)

Thus, according to Graves, the valid administration of baptism requires a local church’s “personal presence and action upon each case” and can only be administered when a local church is “duly assembled”. Any baptism performed apart from direct church action is therefore “null”—that is, invalid. In other words, the validity of baptism is dependent on the personal presence and action of the congregation in every case.

But although J.R. Graves is a respected authority among Landmark Baptists, even his assertions must ultimately be tested by scripture. What scriptural evidence can we bring to bear upon these claims?

It turns out that Graves’ direct church action model of baptism can be easily disproven by the baptism of the Ethiopian eunuch recorded in Acts 8. By now in our series, we’re already very familiar with this account. Philip was led by the angel of the Lord to a eunuch traveling back to Ethiopia from Jerusalem. Philip preached Jesus to the eunuch, and the eunuch believed. The eunuch asked to be baptized, and Philip baptized the eunuch.

We might ask, was the baptism of the Ethiopian eunuch valid?

According to Graves’ theory, it could not have been. No local church was present when the eunuch was baptized. No local church examined the eunuch to decide whether he was qualified to receive baptism. And even if Philip were an ordained minister of the church at Jerusalem, his ordination would only have qualified him to administer baptism when specifically called upon by the church to do so.

But of course, this is all absurd. Obviously, Luke intends for us to understand that the baptism of the Ethiopian eunuch by Philip was valid. There is absolutely nothing in the text which would even suggest otherwise.

It should be abundantly clear that Graves’ direct church action theory is false. These special requirements did not arise from the text of scripture—they arose from the mind of a man.

During his personal ministry, Jesus reserved his harshest criticisms for the Pharisees, who elevated their own traditional rules to have the same authority as scripture. Once, the Pharisees confronted Jesus because his disciples did not wash their hands before eating, in violation of one of their man-made rules. Jesus answered them:

Well hath Esaias prophesied of you hypocrites, as it is written, “This people honoureth me with their lips, but their heart is far from me. Howbeit in vain do they worship me, teaching for doctrines the commandments of men.” (Mark 7:6b-7)

May God help us never to perpetuate as doctrine the commandments of men.